Cuckoo - harbinger of spring

There’s a feeling I get sometimes, where my skin turns to eggshell and a squawking bird tries to burst out, my fingertips ache because the feeling won’t fit inside. It’s not attached to any one particular feeling, it can be lust or grief or joy or despair or giddy excitement, it’s just a certain bigness of feeling. Most winters the bird stops squawking and hibernates (because it’s a metaphorical bird it can hibernate if it wants to, or maybe it’s a Common poorwill) the feelings shrink and mute in colour, and I feel less like myself and miserable (in that small stuffy grey room kind of way) because of it. The bird stirs from its slumber around the time the sap is rising in the trees, and by the time the bluebells are out it’s flying around my ribcage day and night*

Our ancestors (in England) had just two seasons, summer and winter. The four seasons were apparently an import from the continent. Personally, I think we have 7 seasons; summer, penny bun and leaf change autumn, blewit and leaf fall autumn, winter, and then the three springs. First there’s wood anemone and chiffchaff spring, then bluebell and cuckoo spring, and then right on the precipice of summer is the elderflower and swift spring. Bluebell and cuckoo spring is the bit I think of as Giddy Spring.

There’s a coppiced woodland near me that’s the only place in England I ever hear the cuckoo, and even when I was living in London I would make sure to come down and meet giddy spring there. By late April the copse is carpeted in bluebells and sweet woodruff, the song thrushes are battle rapping in the oak trees, the nightingale is singing, the badger cubs have started venturing out, and the cuckoo is calling. I know this time makes birds fly around and squawk and sing in other people's chests too and has done for hundreds and hundreds of years, because of all the songs that celebrate the cuckoo, and what is a song if not the ache in the fingertips finding a way out?

The cuckoos that come to England make an arduous journey over the course of weeks from central Africa (Congo, Gabon, and the Democratic Republic of Congo) to return to their breeding sites. Not all of them make it, some die en-route to us, and some on the way back. Since the early 1980s Cuckoo numbers in England have dropped by 65% (they’ve increased in Scotland however), which means we’re getting less and less likely to hear its call. The reason for the drastic drop in numbers is still unknown, but the British Trust for Ornitholiogy, are doing lots of work tracking cuckoos and trying to get to the bottom of their decline.

Cuckoo - King of the fair

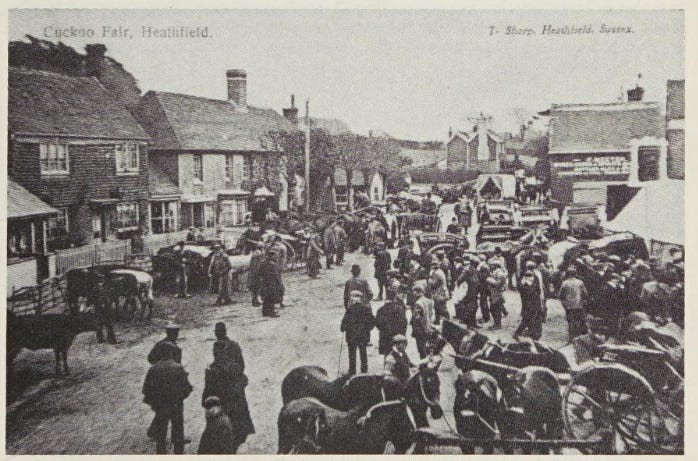

Before we knew about bird migration people held different beliefs about why some birds appeared in the spring and then disappeared again at the end of summer, for cuckoos one of the most prevalent beliefs was that they turned into hawks. In Sussex it was thought that an old woman took care of the cuckoos all autumn and winter and then let them out of her basket** the Heathfield fair on April 14th. The day was also known as Heffel fair, Heffle fair, and Cuckoo Day. Rudyard Kipling, who stayed in the area, wrote about the day in his poem ‘Cuckoo Song’

Tell it to the locked-up trees,

Cuckoo, bring your song here!

Warrant, Act and Summons, please,

For Spring to pass along here!

Tell old Winter, if he doubt,

Tell him squat and square—a!

Old Woman!

Old Woman!

Old Woman’s let the Cuckoo out

At Heffle Cuckoo Fair—a!

Heathfield cuckoo fair started in 1315 and ran as an annual fair for hundreds of years. It was held in the fields and roads around The Half Moon Inn and local historian Alan Gillet wrote that during Heffle Cuckoo Fair Romany caravans would park all along the road from the church selling wares such as horses and clothes pegs.

Until the 19th century there was a tradition among Shrophire coal-miners that as soon as the first cuckoo of the year was heard they stopped working for the day and went outside to drink, to “wet the cuckoo”. It was especially important that the ale was drunk outside (usually on the pit-bank) and a fine was levied on anyone who proposed drinking inside. The drink was called cuckoo ale or cuckoo foot ale (in reference to their zygodactyl feet), and the Salopians weren’t the only ones boozing it up for the cuckoo. There are churchwarden accounts in Mere, Wiltshire from 1565 of some festivity that included lots of ale (as all good church functions used to) and the appointing of a ‘Cuckowe King’.

“John Watts the sonne of Thomas Watts is appointed to be Cuckowe King this next yeare according to the old order, because hee was Prince the last yeare”.

I also read about a cuckoo feast in the civil parish of Towednack in Cornwall that took place on the closest Sunday to the 28th of April (this year the 28th is a Sunday fyi) and check out this quote (from the 1865 book ‘Popular romances of the west of England’) “the feast is now called the Cuckoo Feast or even ‘Crowder Feast’ because the fiddler formed a procession at the church door and led the people through the village.” Crowder (my surname, in case you hadn’t clocked) means someone who plays the fiddle, something that I never mastered (my horrible violin teacher Mrs Cox wouldn’t even let me use the bow).

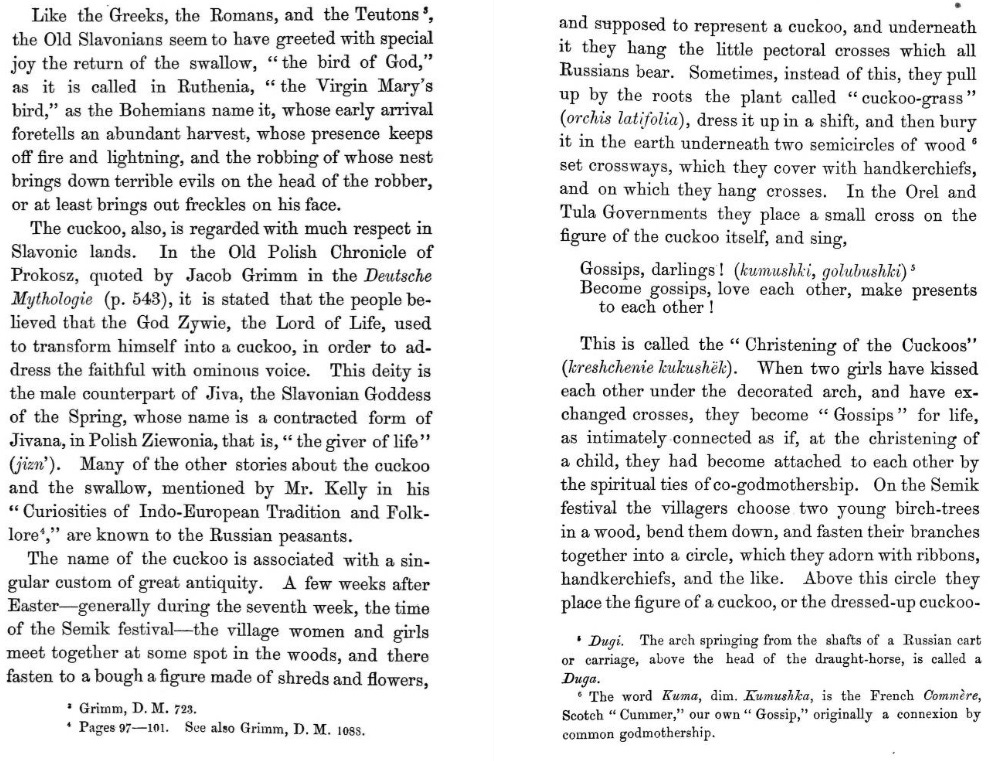

I have mentioned before that I tend to get very carried away with research (I think the length of this and the references list attest to that), and looking into cuckoo celebrations totally consumed me for a few days. I found out about lots of cuckoo celebrations around the world but a lot of the time I either had to use google translate on academic papers written in languages I don’t speak or rely on English men from the 19th and 20th century writing about other countries' customs (often heavily biased and not entirely reliable***). That being said I’ll share with you the bits I found and if you have any knowledge of them (or others) please share them with me. In the 1970 book ‘The folklore of birds’, Edward Allworthy Armstrong wrote that some Siberian tribes date their spring ceremonies by the call of the cuckoo, and in ‘The songs of the Russian people’ William Ralston Shedden-Ralston wrote about a “ singular custom of great antiquity” that happened in Russia, generally during the Semik festival, that included a “christening of the cuckoo”. I also read about a Hindu festival where clay idols of cuckoos are worshipped as a form of the goddess Sati to help attract a loving and caring husband.

Cuckoo songs

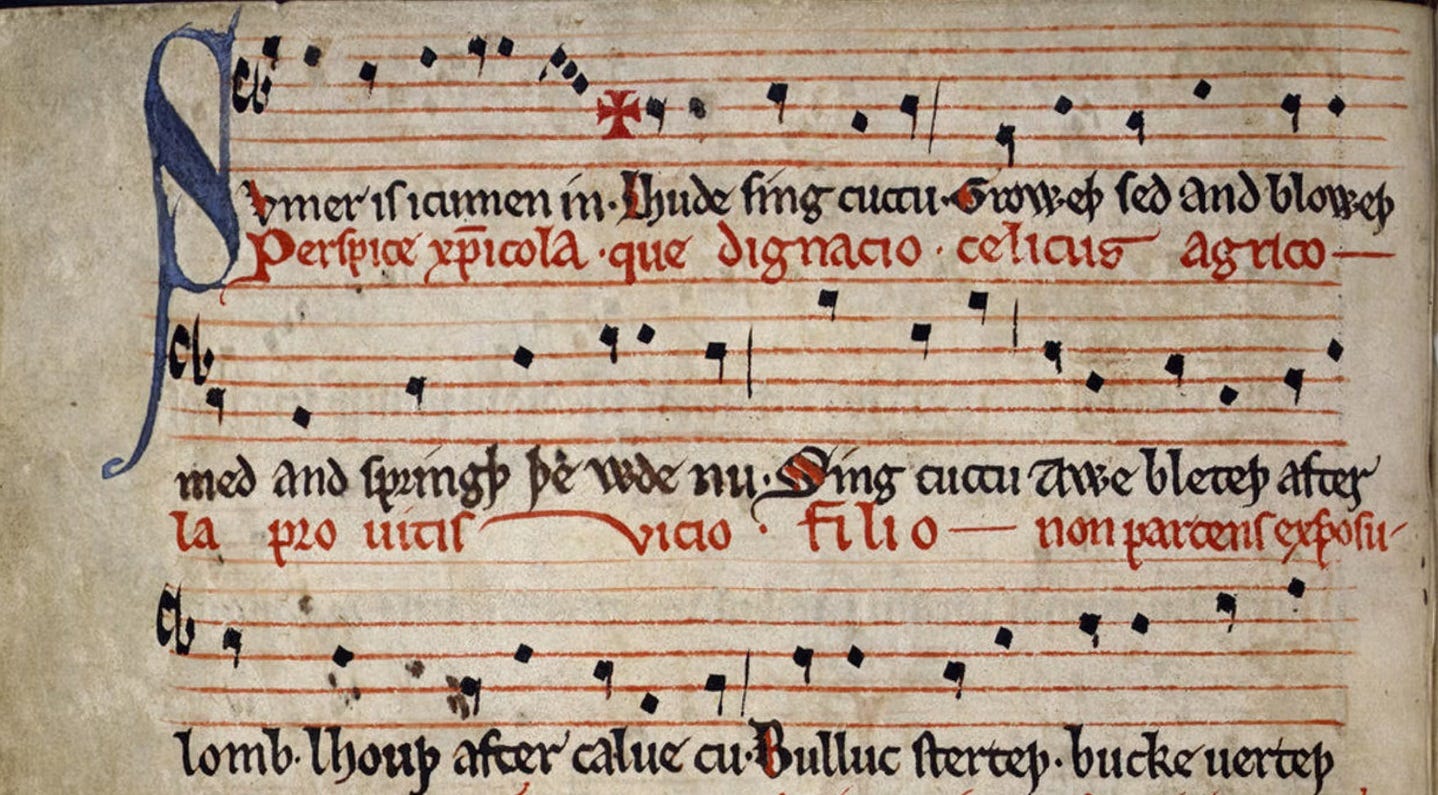

If you’ve seen The Wicker Man you may be familiar with (a menacing version of) the oldest known song (more specifically it’s a ‘round’) in the English language. ‘Sumer is icumen in’, an ode to cuckoos and the arrival of the warmer season, was found in a manuscript (Harley 978, which also contains a glossary of herbs, recipes, and medical texts) which has been dated to approximately 1260, but who knows how long the song had existed before that?

The translation (since the original is written in Middle English) goes;

Summer has arrived, Loudly sing, cuckoo! The seed is growing And the meadow is blooming, And the wood is coming into leaf now, Sing, cuckoo! The ewe is bleating after her lamb, The cow is lowing after her calf; The bullock is prancing, The billy-goat farting, Sing merrily, cuckoo! Cuckoo, cuckoo You sing well cuckoo, Never stop now. Sing, cuckoo, now; sing, cuckoo; Sing, cuckoo; sing, cuckoo, now!

Remember how I mentioned that England used to only have two seasons? The ‘sumer’/summer mentioned here is the season that started on Spring equinox (my birthday) and finished on the autumn equinox (my mum’s birthday).

“Two linguistic cautions are in order. First, notwithstanding the apparent meaning of the word with which the lyric begins, this is indeed a text for springtime - as we would expect from the theme, the cuckoo arriving in England during April. There is no contradiction, because in Middle English sumer was the only word available to describe the period between the vernal and autumnal equinoxes. The word spring to refer to the season is not recorded in English until the mid sixteenth century.” - David Crystal in The stories of English.

The second linguistic caution he goes on to discuss relates to the word fart, since some translations go with “the stag cavorts” rather than the billy goat farts.

I chose this version specifically because it’s the Ralph Vaghan Williams arrangement, and he grew up in the place where I go to hear the cuckoos every year, so it felt particularly apt. There are lots of great versions out there though, including one by Richard Thompson.

If you’ve not seen The Wicker Man, maybe the cuckoo song you’re most likely to be familiar with is the old traditional song simply called The Cuckoo (Roud 413), which has been sung by Shirley Collins, Anne Briggs, Townes Van Zandt, Bob Dylan, Janis Joplin, Ramblin Jack Elliot, Rory Gallagher, and so many more. Most American versions include floating verses from another traditional folk song; Jack of Diamonds. English folk singer Shirley Collins, who learnt the song from her great grandmother, sang it on her 1959 album ‘Sweet England’, but I think Anne Briggs version is my favourite.****

I made a spotify playlist full of songs about cuckoos that you can listen to here

I know our ancestors welcomed the arrival of the cuckoo because it was the harbinger of warmer weather, but now that we know about the migration of birds we should also celebrate that it survived the perilous journey it made across thousands of miles to be here. It can be profoundly painful to be a witness to all the suffering in the world, especially at the moment. But if we owe it to others to bear witness to their suffering, I think we also owe it to ourselves to bear witness to the joy the world has to offer and to seize it wherever we can find it, eat every crumb of it up. So if you’re lucky enough to hear a cuckoo call you should celebrate it; sing a song, compose a song, dance a mad jig, take the day off work to sit outside with your friends and drink some homebrewed ale/mead/gruit/nettle beer (or an exciting non-alcoholic drink if you’re sober) to ‘wet the cuckoo’.

Zygodactyl Footnote section

My mum, who is a lot more succinct than me, recently summed up a sentiment that I took paragraphs to explain. I mentioned to her on the 5th of April that it was 30 years since Kurt Cobain had committed suicide, “seems a shame to kill yourself in spring”, was the response.

* I realised a few paragraphs after writing this, when I was going for a wee (not that you needed to know that) that it might read like I’ve slightly ripped off the bluebird in Bukowski’s heart but I don’t think they’re the same kind of birds.

** In ‘Mythological bonds between East and West’ Dorothea Chaplin writes that this basket might represent the yoni. Back when this newsletter was going to be a zine I was planning the front cover to be a drawing of a bunch of cuckoos flying out of a vagina.

*** to give an example of the bias I’m talking about, here is an introduction from a 1906 Folklore society publication “To those who are familiar with the customs of savage and semi-civilised nations”.

**** 2 things, 1. I suspect anything Anne Briggs covered would become my favourite version of it. 2. I don’t want to reduce an incredible artist to their role as muse, people box talented women into that role far too often. But I can’t help but mention that the singer of one cuckoo song (Richard Thompson) wrote a beautiful (but also infuriating, to me anyway) song about the singer of another traditional cuckoo song (Anne Briggs).

Reference List

Burne, C. S. and Jackson, G. F. (1883) Shropshire folk-lore: A sheaf of gleanings. Trübner and Co.

Chaplin, D. (2022) Mythlogical bonds between east and west. Legare Street Press.

Crystal, D. (2005) The stories of English. Harlow, England: Penguin Books.

Gillet, A. and Russell, B. K. (1990) Around heathfield in old photographs. Abergavenny, Wales: Sutton Publishing.

Hartshorne, C. H. (2023) Salopia Antiqua: Or, an enquiry from personal survey into the ’druidical, ’ military, and other early remains in Shropshire and the north welsh borders; With observations upon the names of places, and a glossary of words used in the county of salop. Legare Street Press.

Hunt, R. (ed.) (1865) Popular romances of the west of England: Or drolls, traditions and superstitions of old Cornwall. London: Chatto & Windus.

Johnson, W. H. (2009) The superstitions and curious beliefs of old Sussex. Lewes, England: Pomegranate Press.

de Kay, C. (2022) Bird gods. Legare Street Press.

Nance, D. A. (2022) “Sacred kings of the Picts: the last cuckoos,” Scottish geographical journal, 138(3–4), pp. 271–290. doi: 10.1080/14702541.2022.2120628.

Seasons in the middle ages (2020) issuu. Available at: https://issuu.com/magdalenecollege/docs/magdalene_matters_issue_45/s/10577792 (Accessed: April 9, 2024).

Wilson, J. D. (2018) Understanding the decline of the common cuckoo, British Ornithologists’ Union. Available at: https://bou.org.uk/blog-wilson-cuckoo-decline/ (Accessed: April 9, 2024).