We're in the redwing and rot half of the year - pt 2;

Birch, please. Sap, mead, redheads, fecundity, rot, and slip sliding away. A year, and life, in birch. Birch in a year, and lives.

After contracting down to the smallest they can be, the days have been expanding and this week I’ve really noticed the extra light. The northern hemisphere started its big inhale on the winter solstice, and it will keep on filling its lungs with light until the summer solstice, when the sun hands the baton over to the moon and the exhale of shortening days and dimming lights begins. Then repeat.

Inhale, exhale, inhale, exhale, until the end.

In honour of the light returning, the second part of We’re in the Redwing and Rot part of the year1 is about birds that bring fire and light with them, and birch; the brightest tree of all. Etymologically, the name ‘birch’ comes from the Proto-Indo-European root Bhereg - to shine; bright, white, and you only needed to look at one in the snow and winter sun last week, or the full moon reflecting off it’s bark on Monday, to see that brightness in effect.

Below

My grandparents would never have met if it wasn’t for a tiny bit of coppiced woodland in Surrey, and that land would never have known our footprints if my great-great grand-uncle hadn’t died in a freak toboggan accident. My great-great-granny Emma needed a space to hold her grief, and because of that, the descendant of jewelers and clock-makers from the city (my gran Jane) met the descendant of land-workers from the countryside (my grandad Luke), and started a family.

There’s a good chance that if it wasn’t for a dead boy and some dead birch (the wood most often used for toboggans) I wouldn’t exist, and neither would my mother, brothers, uncles, and cousins. I imagine that had he lived he probably would have started a family, and there’d be a lot of life from his life, but as it was there’s a whole lot of life out of death instead.

I do this sometimes, start meandering down that slippery path of thinking about all the people who had to be born, and die, and fuck, and fall in love, and fall out of love (and plenty who probably didn’t love at all), and slide in the wrong direction for me to be born. For every living thing to come into being, there are so many millions of little things that had to happen first. Once you start looking at it all, it’s hard not to feel both tiny and gigantic at once; the starling and the murmuration, the single fruiting body of fungus and the whole forest.

The woodland that I owe my existence to is called Coppice. It’s less than an acre in total, and is located between one village named for its Oak trees and another named for its Yews, near two old Roman roads and the reputed site of a 9th century Viking battle2.

Coppice is still looked after by my family, second cousins and all. “Looked after” because coppiced woodland (which is great for dormice, wood anemones, bluebells, nightingales and other warblers) is very much a collaboration between people and the land. Coppice wouldn’t be the same bit of land without my family, and my family wouldn’t exist at all if it weren’t for Coppice.

The forest is death itself. Have you seen that everything that grows in the forest is growing on the rotting bones of what came before? This is the rule of the forest. Eater is eaten, death is life. Step into this world, and beware; you will grow, you will thrive, you will surrender to the cycle and then die…. in the forest - Josh Schrei from his wonderful podcast The Emerald (the episode this comes from is called Awake in the forest of dangers and wonders).

It would be wrong to call Coppice a forest. I have friends whose gardens are bigger, but it too is built on the rotting bones of what came before.

John Richard Gillett died on his toboggan in January 1928, aged 15. His elder brother, my great-grandad Will, bought Coppice in 1929 from some chicken farmers whose business had failed. In the 95 years since the land entered into our family cartography, we’ve added to the humus and the history; ashes of loved ones and also of parties, the bones of beloved dogs, the rotted down vegetal matter of hundreds of spring and summer flowers, and old trees.

History has been unearthed there too. Just beyond the boundary of Coppice, in the bit of land where the old brickworks have been colonised by birch, buddleia, and lichen, near the quarry pit lake, the most complete spinosaurid dinosaur skeleton in the UK was discovered in the 1980s; the holotype specimen of a theropod dinosaur called Baryonyx walkerei.

20 or so years ago my mum took 2 silver birch saplings (Betula pendula) from that land, from the clay soil that has been fed by dinosaur meat amongst other things, and planted them in her garden. She planted them either side of the driveway, just after I moved out.

Since I moved back in with her a couple of years ago, the trees have started to feel like part of the family too. I love looking out of the window when I wake up, and seeing what seasonal wear they’re donning, and how many birds are adorning their branches.

A year in Birch

In January and February of 2024 a troupe of redpolls (Acanthis flammea) visited the garden dail, to swing like acrobats on the end of tiny birch twigs, and feast on the abundant birch seeds. Redpolls typically eat about 40% of their bodyweight in seeds just to stay alive in the winter, and they favour the seeds of birch and alder trees.

As is so often the case with red-headed and red-breasted birds, the redpoll features in a story about bringing fire to people. The story I read, which came from 19th century Alaska3 via the naturalist and ethnologist Edward Nelson, goes that the redpoll braved the fearsome bear that was guarding the perpetual fire, in order to take a small ember and bring it to the people.

Birch trees are a fast-growing pioneer species, they were one of the first species to re-colonise Britain after the glaciers of the last Ice Age receded, and they are among the first trees to grow after devastation by forest fires, or large-scale felling for commercial purposes.

In 1943 the Forestry Commission calculated that five trees were required to allow a single soldier to fight4. This led to a lot of bare ground for birches to grow on, which in turn led to an increase in redpoll numbers in the UK. The original baby boomers. Come the 70s, the post-war birches were muscled out by larger, slower growing trees. The combination of this drop in birch numbers, as well as changes in agricultural practices (meaning less weed seeds) saw the British redpoll population drop by 86% between 1970 and 2013.

So, the redpolls bring fire, and from fire redpolls emerge.

At the beginning of March I invited some of my friends to come and pick wild garlic, eat around a fire, and tap one of the birches at Coppice with me.

Right after the last starling murmurations of the winter, but before the sweet violets come out, buds on the birch tree will start to swell. The swelling of the buds means that the sap is rising, the water and nutrients that the tree has drawn from deep down in the soil are rushing up through the trunk, and into the branches and twigs, so that it has energy to grow and put out leaves.

We adorned the trunk of a birch with a garland of dried strawflowers, played her some Bjork songs, left offerings, and asked permission before tapping her. Michael used the handheld drill that Sophie brought, and bored just slightly into the tree, at an angle. Sap gushed out.

The sap flowed while we gathered wild garlic (Allium ursinum), it flowed while we listened to a woodpecker (Dendrocopos major) drumming, and it flowed while flames danced from the fire that Sophie and Ben had built. When the bottle had filled with enough sap we plugged the hole back up, thanked her, drank, and washed our faces with the sweet water, then put some aside to take home.

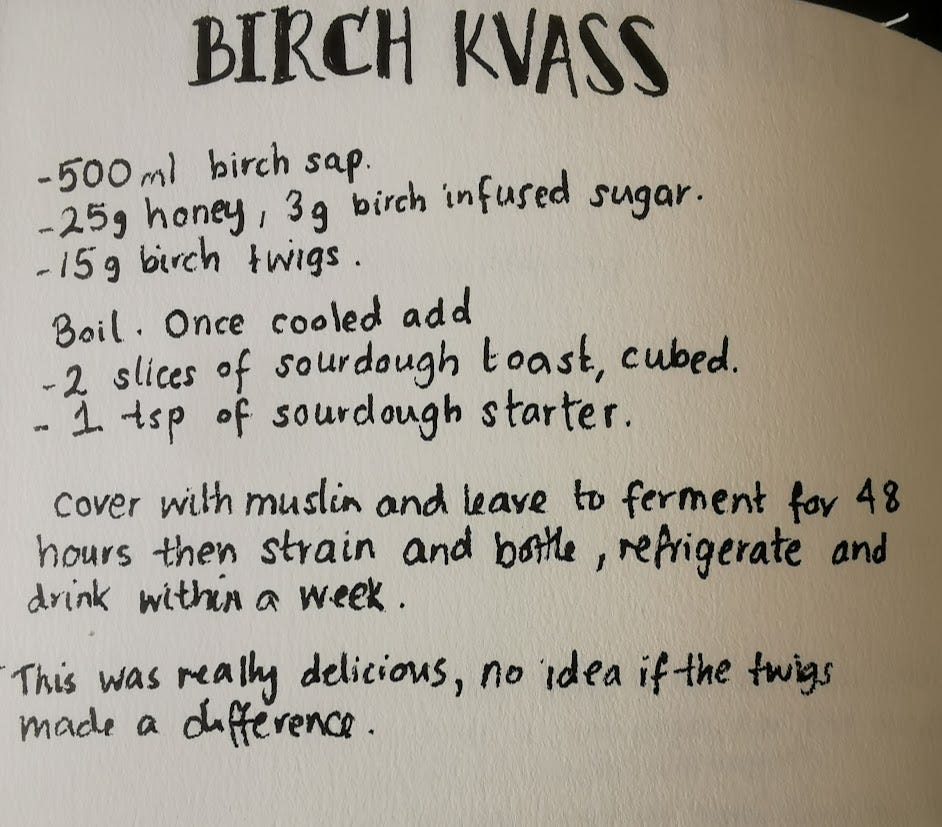

I fermented the sap I took home; made kvass with some of it and sweet violet infused mead with the rest. It wasn’t my first time making mead with birch sap, a few years ago I made a sickly sweet birch sap and meadowsweet mead, based on a drink that was buried with a Bronze-age woman in Scotland. Neither of the meads have been great successes, but the kvass was amazing.

Sometimes, observing the other life forms that inhabit the world helps me to make sense of myself too. The sap was rising in all the trees, and I felt sure that the sap was rising in me too. I felt full of promise, a place which has always felt right on the cusp of feeling full of threat.

On my birthday (Spring equinox - March 21st) I went for a walk to the same hill where I heard the first cuckoo, redwings, and nightjars of the year, and Merlin (the app, not the magician) claimed to have picked up a Lesser spotted woodpecker (Dryobates minor), though I’m doubtful that it was accurate.

It’s been an ‘unsustainable’ year for the Lesser spotted woodpecker, according to the Woodpecker Network, who said “Despite massive efforts to find them, only nine nests were reported and monitored, and these were relatively unsuccessful." The Lesser spotted woodpeckers need dead wood to nest in (Birch, Alder, Poplar, Willow, Sycamore, or Beech), proximity to water, and insects to eat. Apparently April and May were too wet and warm, and there weren’t enough defoliating caterpillars for them to feast on.

All spring long I felt that sap pulsing in me. I just knew that summer was going to be perfect and warm, and full of plants and life, and that I would harvest so much and preserve everything. But all the build-up felt like it amounted to nothing, the buds of promise did not unfurl, the drumming did not reach its intended crescendo, and I felt like a dud firework.

I’d be shocked to meet anyone whose 2024 went the way it imagined they would, or any year in this decade so far. We’re all trying to learn how to live in a world that is shifting every day.

I may have not sprung into life, but the birches did. Their buds burst into pale green toothed leaves, the male catkins used the wind to help them pollinate the plump green female catkins5, and the birch Aphids feeding on the tree provided food for nestling tits and warblers.

From April through to June, when the birch trees are at their most fecund and verdant, they are used, both ritually and decoratively, in celebrations all over Northern and Eastern Europe.

Birch once played a part in our spring and summer fire and fertility festivals in6 the British Isles too. A 1603 survey of London described how on St John’s eve (around the summer solstice) every man’s home was decorated with “green birch, long fennel, Saint John's wort, orpin, white lillies and such like, garnished upon with garlands of beautiful flowers”, all illuminated with oil lamps. On May Day (also known as Beltane) doorways were decorated with hawthorn blossom and birch boughs, and the earliest record we have of a British Maypole comes from a 14th century Welsh poem that talks about the birch tree that was cut down to make it.

At the school I went to, just a few minutes down the road from Coppice, May Day was the best day of the whole school year. A May Queen would be chosen to lead the parade, and for weeks before the big day we’d all practice the dance around the Maypole, weaving in and out with coloured ribbons in our hands and little plimsolls on our feet.

I did nothing for May Day this year, there was no fire jumping or dancing coloured ribbons, yet the best moment I had in May still managed to involve birch, fire, and dancing colours.

I was relieved when summer was creeping out of the window in 2024. No more trying to make the season be something it didn’t want to be, or me be something I couldn’t seem to be. I told myself autumn will be great; I’ll make bottles of rosehip syrup, I’ll make my tastiest hawthorn ketchup yet and gift it to all of my friends at Christmas, and I’ll pick and dry so many porcini that I can feast on them all year long.

The Porcino (Boletus edulis) is also known as Cep, Penny bun, and King bolete. I don’t know why I tend to call them by their Italian name (Porcini is the plural by the way), only that it’s a word that my mouth greatly enjoys the shape of, and I try to say as many of those kinds of words as possible.

My dad used to take me to look for field mushrooms and parasols when I was a kid, but it was my mum who introduced me to the really choice edibles; Bay boletes, Chanterelles, and Porcini. She taught me that if I want to find a Cep then my best bet is to find ancient woodland with acidic soil, to look near birch trees7, and to keep an eye out for Fly agaric (Amanita muscaria) toadstools. Once you spot the bright red cap of the Fly agaric, the toasty brown pileus of a Penny bun is often close by.

Both Boletus edulis, and Amanita muscaria have symbiotic (specifically ectomycorrhizal) relationships with a variety of trees, including birch. I’ve heard Amanita muscaria referred to as the birch trees ‘life partner’.

The fungi form a sheath of mycelium around the roots of their tree partner, which allows them to absorb nutrients from the tree, and because they can cover a much larger area than the trees roots, in exchange they are able to forage for more water for the tree.

Mycorrhizal fungi have been around for hundreds of millions of years and research suggests that they are the root of all life on land. Underground, mycorrhizal fungi form an extensive network, known as mycelium, of microscopic thread-like strands or hyphae, which becomes far more extensive than the actual roots of a plant. Incredibly, the fungal network can cover up to 700 times more soil than the plant roots alone. Fungal networks also connect individual plants together to share resources in a natural ecosystem, often described as the ‘wood wide web’ for its similarities with the internet or ‘world wide web’. - Sue Fisher in Gardeners world.

2024 was the worst year I’ve known for Boletes, I found no more than ten the whole season. In previous years I’ve filled my basket many times over with Porcini. I’ve dried them out in the dehydrator and filled big jars with them to use in risottos and stews all year long.

In the book Radical Mycology (a gift from a friend who is magic), Peter McCoy suggests that it may be the trees movement of storage sugars to its roots in the late summer and autumn that triggers the fruiting bodies of mycorrhizal fungi to emerge.

If the tree couldn’t spare enough sugars for mass fruitings of my favourite fungi this year, it stands to reason that they won’t have enough to spare for me to tap for their sap come spring, so I will take a year off. I don’t need the birches to be productive every year, I just want them to survive as long as they’re meant to.

Feeling into the rhythm of the year is not just about being a passive observer, ah this bit is beautiful and this bit is sad. It’s part of learning how to live in better accordance with the land; knowing when to sow and when to reap and when to let things be. When to chop a tree down, when to coppice it, and when to leave the deadwood standing. As with all learning, it’s a lifelong process, and I still get shit wrong all the time.

My friend Wiggy, and her wonderful husband Sam, came down for a walk and a mushroom mooch in October. She came to mushroom hunt with me in 2023 too, and we found masses and masses of Fly agaric, great dizzying circles of them. There is not a way I can describe Wiggy that will do her justice, but she is the most mycelial person I know, bringing whole forests of people together, reaching out to the edges of love to nourish them all. Your world gets bigger when it has her in it.

We offered mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris) at the threshold of the woods, and I taught Wiggy and Sam the chanterelle song (chanterelly relly relly, get in my belly, belly, belly), and the porcini song (Porciiiiini, I want to eat you with linguine. Porciiiiini, find your way to me8), which are the siren calls/song gifts I sometimes use to help me find mushrooms. We sung those as we walked down Wolvern’s lane, an apt name for a howling place, if ever there was one.

We didn’t just sing and look for mushrooms, we also ate cheese sandwiches, drank delicious coffee, and offered some birch sap mead and smoke to the holy spring hidden in the woods. It took miles of walking, and tired feet, and getting lost on the side of a hill to find just two beautiful porcini - one for them and one for me, nestled in the sandy soil by some pine and birch. I got down on my knees to pick it, but kissed its pale brown cap and thanked it first.

In this kiss and thank you is thank you for feeding me and my friends, but also a thank you for sap, for feeding the trees, which in turn feed the insects and birds. Thank you Boletus edulis for birdsong.

While we were walking, talking, and enjoying the sweet smells of rotting and rotten wood, I got a text message. Hi, it’s Jake (your brother). I was thinking maybe we could go for a walk sometime soon, look for some mushrooms and have a chat?

I hadn’t seen Jake since he was a baby, and he vomited on me. He’s 28 years old now. We share a complicated dead dad.9

I sometimes feel like I inherited a family tree from my mum, and a weather pattern from my dad. Maybe that’s why feeling full of promise feels on the cusp of feeling full of threat, because I don’t know if all that build up is a tree about to burst into life, or if there’s a storm brewing. Of course though, that is a reductive way to look at myself, my parents, trees, and storms, all of which are capable of nourishing and destroying (and it can be impossible to zoom out far enough sometimes to see which one is even happening in any given moment).

Jake was 6 when our dad was killed, and I don’t know who he might have become if my dad was still alive, or if we would have been more or less likely to eventually reconnect. I do know that it’s kind of miraculous he’s turned into the sweet, intelligent, young man that I met in October.

I wanted to get more porcini and learn about my little brother, and Jake wanted to find fly agarics and learn about his family, and so I suggested we go for a walk on the site of an ancient hillfort. As we walked, he told me about his life, his maternal grandparents, his sister (with the same name as me!), and his love of metaphysics and learning in general, and I told him about all the versions of our dad that I knew, and about his paternal grandad, and aunt, and ancestors.

Despite it being peak fungi season in one of my best spots, we found very little of anything besides a few amethyst deceivers, and some dead birch trees covered in Birch polypore (Fomitopsis betulina).

Whilst some mushrooms are there to help trees and plants thrive, there are others who feed on their death. Birch polypore falls into the latter camp, it is saprotrophic and helps with the decay and decomposition of an already dead or dying tree (it is occasionally parasitic on weakened living trees too). It is not a tasty mushroom10, but is valued instead for it’s practical and medicinal properties.

I was a little bummed out not to find the mushrooms we wanted, but I love seeing the sabropes, and being reminded of some of the medicine that can come from the rotting of old structures.

Birch polypore’s medicinal properties most likely account for why some was found with Otzi the Iceman. Otzi is Europe’s oldest natural human mummy (Homo sapiens). Among other items, he also had birch-bark baskets, and a well-made copper axe affixed to it’s yew (Taxus baccata) handle with birch tar.

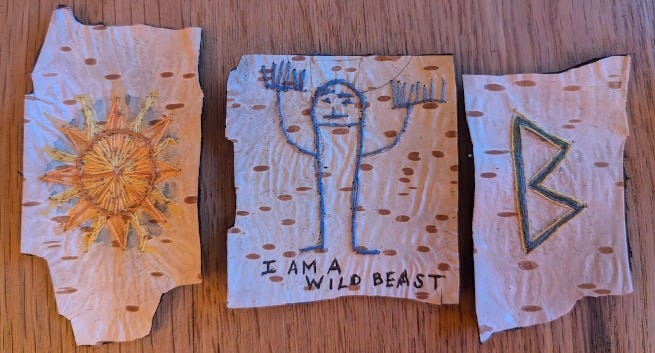

Otzi’s baskets, tools, and fungi are not the only historically important artefacts that come from the birch tree. The oldest Buddhist texts yet discovered, dating from around the first century CE, were found written on birch bark, and stored in clay jars in Pakistan. In the 1950s archeologists in Russia found the homework of a little boy (Onfim) who had lived in 13th century Novgorod, all of it was written and doodled on birch bark.

My brain was foggy in November (anticyclonic gloom/world-is-doomed-blues) and I couldn’t write (sorry11). I could write, but I would look at a sentence I’d just written and then say to myself, what kind of moron writes a sentence like that? Repeat ad infinitum.

A friend sent me a clip of Joni Mitchell saying that she never gets writer’s block because she ‘crop rotates’ by painting. The vegetal analogy and ease of this solution spoke to me, so I gathered my art supplies and got ready to Joni the fuck out of my writing.

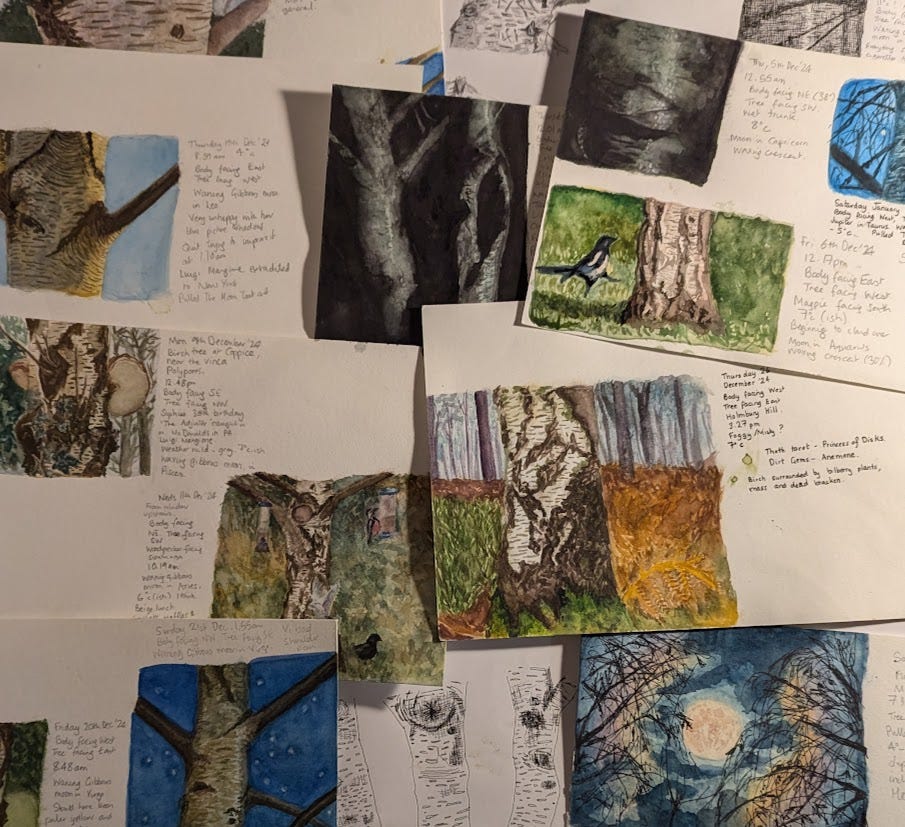

I drew one of the birch trees in the garden, and added a bit of writing about what phase the moon was in and which direction my body was facing, in order to root myself into the time and place I was in the world for that moment. I did not magically wake up the next day able to write (without self-flagellation), so I drew another part of the birch tree.

After finishing my second drawing, I was scrolling Instagram reels (maybe part of the reason I can’t concentrate on writing), and saw another clip. This time it was Martin Shaw (doctor of mythology Martin Shaw, not Judge John Deed Martin Shaw) saying “we make things holy by the kind of attention we give them.”

The birch tree doesn’t need my help to become holy, but this clip inspired me to carry on drawing them whether my writer’s block resolved or not. It helps me to have something to be devoted to, something to pay attention to that makes me feel good, I am also hoping it will make me better at painting and drawing (even if that’s only birch trees).

I’ve been drawing or painting them now every day since late November, and the attention has been deepening my relationship to the birches too, to the tree that I think of as my family tree.

The birch trees acted as a kind of advent calendar for me in December. When I was at home I was excited to see what new aspect of them I could uncover, maybe the silhouette of catkins against the full moon, golden hour light on the bark, or a constellation between branches, and when I was out it was a fun challenge to focus on trying to find a birch tree.

December has the darkest days in the northern hemisphere, and when things get really dark you want to make a place for the light in your home, heart, and hearth. It was, as it always has been, a month of celebrating light around the world. People gathered at Stonehenge (and Newgrange12) to welcome the sun back on the winter solstice, Hannukah and Kwanzaa candles were lit, Christmas lights were strung up on spruce and fir trees, diya lamps were lit for Karthigai Deepam, and in Sweden, my friends celebrated St Lucia day on December 13th.

I thought of the girls of St Lucia day, dressed in their white gowns with crowns of candles on their heads, when I saw the goldfinches in one of the birches the other day. Naked, but for her peeling white bark and and some bird shit, a whole charm of goldfinches formed a golden crown as they sat in the top of her branches, illuminated by the afternoon sun.

“One of the medieval Latin names for goldfinch was ‘Lucina’ - the bringer of light. Borrowed from the nightingale. Associated with Goddess Lucina (title or epithet given to Juno).

In The Floure and The Leafe, a slightly later poem but one which uses many older conventions, the goldfinch is associated with the medlar, a fruit which according to popular expression “had to be rotten ’er it was ripe,” and which was the subject of many ribald puns, particularly in Elizabethan and Jacobean drama later. In the poem the goldfinch leaps prettily from bough to bough of the medlar tree, eats the buds and flowers, and sings. Here the bird symbolizes indolence and worldly pleasure, and as such is a perfect symbol for Perkyn Revelour. - Birds with human souls by Beryl Rowland.

Ahead

The Oxford English dictionary made ‘brain rot’ their word of the year for 2024. Brain rot is defined as “the supposed deterioration of a person’s mental or intellectual state, especially viewed as the result of overconsumption of material (now particularly online content) considered to be trivial or unchallenging.”

Nobody could call Joni Mitchell or Martin Shaw ‘brain rot’, but I’m not immune to overconsumption of trivial content online. However, my word for 2024 would simply be ‘rot’, I expect it will be in 2025 too.

In part 1 I wrote about the grief that is part of paying attention to the world. This perceived brain rot is a product of wanting to avoid watching the real rot of everything we know. Rot when you don’t know what will grow out of the old structures that need to come down.

I’m not against turning away and seeking comfort, a lot of my winter so far has been spent watching Northern exposure and eating stew with suet dumplings. I am someone who is terrified of death and change, but I am living in a world that’s changing all the time, and where everything and everyone will die regardless of my fear. I am also living in a world going through a mass extinction, and so I’ve got a lot more to learn about embracing rot, and about getting comfortable in the dark.

I’ll be reading and listening to people like Sophie Strand, who talks about becoming a compost heap, and Dougald Hine, who speaks about becoming ‘good ruins’, and Bayo Akomolafe, who says “the myth of mastery now has to be composted.”

The birch is a great teacher too. It is often spoken of as a symbol of renewal and regeneration, but it could just as easily be a symbol for interdependency and the whole network of beings you need to live well or live at all, or how to rot and make good ruins.

I went to Coppice recently, and realised how few birch trees we have there now in comparison to when my grandad painted his picture. It is a connection to him to paint birch trees too. The one I chose to paint for that day was dead, and covered in fungi (99% birch polypore, but there was some purple Ascocoryne sp too) and ivy. Crawling up the tree, towards the heavens, was a tree slug eating the lichen and moss that abounded on the trunk.

When alive, the birch tree supports over 300 species of insects, as well as birds. In its death, both the fungi helping to rot down the tree and the decaying wood itself are food for insects, which are food in turn for birds like woodpeckers and nuthatches.

In learning how to sit comfortably in the darkness, I’m still going to make space for the light of the birch tree though. I’m going to keep drawing and painting them, I’m going to leave them offerings and thank them and my ancestors for my life, and I’m going to plant three new ones at Coppice this month.

Maybe this spring we’ll be lucky and have woodpeckers making their home in the dead birch tree we have there.

When I first wrote this it was much more related to part 1, but it has gone through so many changes since then it probably should have just been a separate piece.

A battle where the West Saxons were led to victory over the Danish Vikings by King Æthelwulf. It is contested whether it happened here or in a village with a similar name in Hampshire, but there is more documentation that points towards Surrey.

I’m not sure which people because he used a general term, but I did get very sidetracked trying to find out by learning the names for redpoll in Tlingit and Athabaskan, so that I could google it, which of course meant reading through whole dictionaries and learning about language families.

Does the way I’ve worded this kind of imply that the soldiers needed the permission of five trees? Maybe we should employ that for any future wars.

The male and female catkins both grow on the same tree, as birch are monoecious. The female catkins change colour once pollinated, to a dark red-brown colour.

in? on?

Often they seem to also have Holly growing nearby.

I also taught them the Pineapple upside down cake song that I have composed. I am including this as a footnote on the off chance that some Don Draper type with a pineapple or glace cherry account would like to buy one of the all-time great jingles from me.

One of (many) reasons this has taken so long is that it turned into another dead dad post, and I thought that might be a bit boring and repetitive. If you want dead dad stuff you can read this. This piece once had multiple paragraphs about the art of flamenco in it too, and the history of the Sacromonte caves, in fact I think it was maybe once mostly about flamenco. Even with all the editing it's still ended up stupidly long. 2025 resolution, get better at that whole brevity thing.

The first time I made birch sap kvass, I first made a tea with birch polypore and the end result was actually delicious, but generally speaking it is not nice to eat.

I’ve paused paid subscriptions and won’t turn them back on again until I’m in a regular rhythm of writing.

and plenty more places, I’m sure.

Love the birch observations...and the idea of "crop rotation" for creative block. Thank you for this post!

I love the idea of collecting sap while harvesting wild garlic. Thank you for a fine read